Overview

Recommendations

Next Steps

Social media

Illegal and Immoral: What We Can Learn from Al Capone & Co.

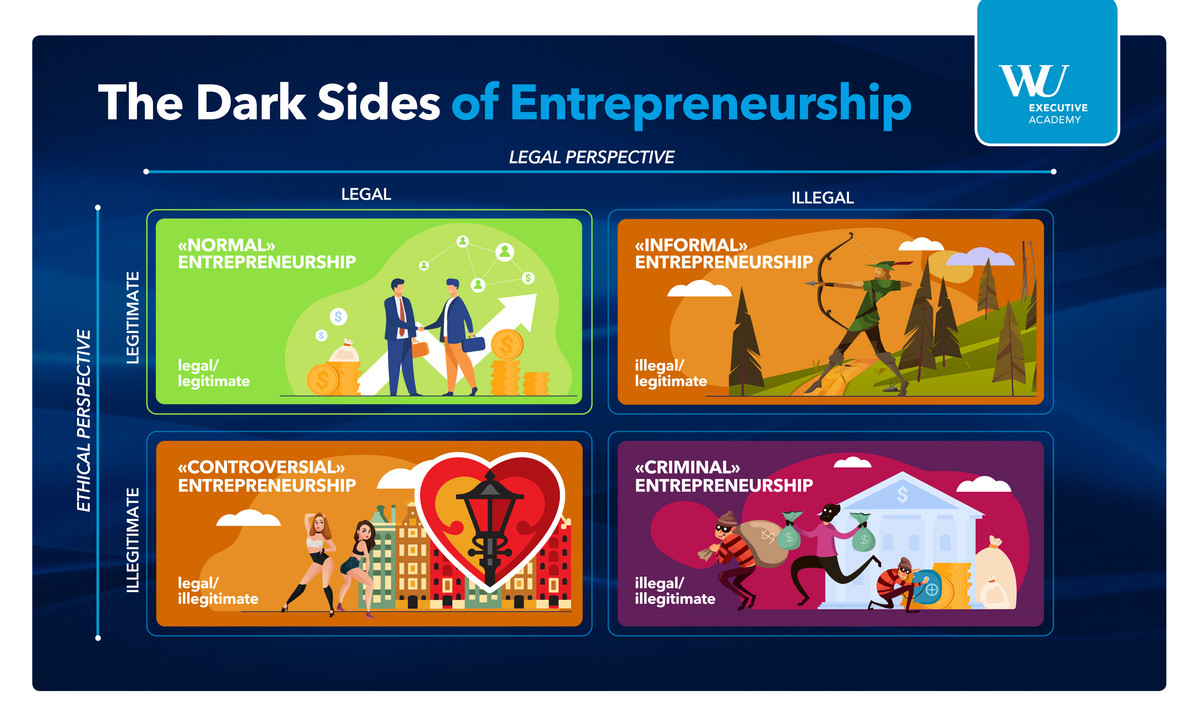

When we talk about entrepreneurs, we usually think of the likes of Elon Musk, Steve Jobs, and Jeff Bezos, whose innovative minds have created progress, wealth, and jobs. But there are also innovators who successfully operate outside the bounds of legality and existing conventions, exploiting new business opportunities with a great deal of creativity and energy. Around the world, more and more researchers explore in which ways people engage in so-called dark entrepreneurship, the lessons to be learned from them, and the conditions that allow to turn such borderline endeavors into something that benefits society; in other words: the light that comes with the dark.

In the third part of this series, Nikolaus Franke, Academic Director of the Professional MBA Entrepreneurship & Innovation at the WU Executive Academy, explores criminal entrepreneurship, i.e., business endeavors that are both illegal and immoral.

We are fascinated by crime. A representative survey by the polling organization IMAS found that 70% of Austrians read crime novels. The German TV station ZDF commissioned the journalist Glenn Riedmeier to analyze their broadcast in the year 2015. He found that it contained more than four and a half thousand murders – ten times the actual murder rate in the country. Millions of people across the globe marveled at the clever heist plots of the Ocean’s trilogy or the “Money Heist” series. And the Grand Theft Auto PC game has sold more than 240 million times.

Many entrepreneurs make it a habit to question rules. The question is: does this include legal stipulations? In a frequently quoted longitudinal study, Zhen Zhang and Richard Arvey investigated whether a criminal record in a person’s youth was a predictor for whether they would become a manager or entrepreneur later in life. It turned out that modest rule breaking (e.g. a DUI offense, getting caught up in fights at or expulsion from school, etc.) was significantly more frequent among entrepreneurs than managers. When it came to real crime (such as theft), however, there was no difference. The conclusion we can draw here is that (future) entrepreneurs are in fact more likely to test legal limits, albeit only in comparatively harmless ways.

There are also criminals who act as entrepreneurs. Some crimes are based on innovative ideas, and in a way, these offenses constitute an instance in which the culprit identified and exploited an – admittedly sinister – business opportunity.

While society rightly condemns such crimes for breaking both legal and moral principles, they nevertheless illustrate important entrepreneurial principles:

Louis Moore, Henry Jackson, and Melvin Cale engaged in a run-of-the-mill crime when they held a gun to the head of the pilot of Southern Airways flight 49 departing from Birmingham, Alabama, on 10 November 1972. At that time, aircraft hijacking was a common occurrence. From about the late 1960s, an airplane was hijacked almost every other week in the US alone. The three men asked for 10 million dollars in ransom money, which the airline was hesitant to dole out. This prompted Jackson to come up with an idea that would change air travel in a lasting way. He threatened to maneuver the aircraft into the Oak Ridge nuclear power plant if the money was not handed over in time. This announcement paralyzed the FBI, the Air Force, and the airline operator. They would not have imagined such a thing in their worst nightmares. There were no precautions or contingency plans for such a scenario; it was all but impossible for them to even imagine the scope of the potential disaster. This innovative threat and the paralysis it caused among the agents in charge were so radical that the hijackers were even allowed to fill their tank and take off again following a stop in Lexington, Kentucky. When the incident finally came to a close in Cuba, the hijackers had “earned” two million dollars.

Another resourceful criminal was Arno Funke, also known as Dagobert (the German name of Scrooge McDuck), who successfully extorted money from a department store chain. He kept police on their toes by coming up with numerous intricate mechanical devices constructed for 30 attempts to hand over blackmail money. Once, he had police deposit the money in a grit bin. Police waited for him in hiding but did not notice when Funke snatched the money from below ground and fled through the sewer system – he had positioned the bin on a manipulated manhole cover. Also entrepreneurs in legal and legitimate fields can’t do without creativity and novel ideas; they are what makes them competitive. Steve Jobs', Dietrich Mateschitz' and Walt Disney's huge successes were not least due to their ability to surprise customers with something they would not have imagined in their wildest dreams.

In 1920, Charles Ponzi , a seemingly respectable gentleman, lured clients in Boston with the promise of a 50% interest rate accrued in only 45 days. And, lo and behold, the first investors did in fact receive as much money. Ponzi paid them with the contributions of new subscribers to what they saw as a dream-come-true system. This way, he accumulated an impressive sum (an equivalent of about 200 million euros today) within only a few weeks. It was not until the scheme imploded that the world learned about the largest financial scam in the history of time. To this day, the term Ponzi scheme refers to any kind of pyramid scheme. This dimension of deceit was only trumped by Bernie Madoff in 2008. His actions caused investors’ losses amounting to 65 billion dollars, bearing proof to the fact that it can pay off to copycat – at least for some time. It is simply astonishing how con artists such as Victor Lustig, who “sold” the Eiffel tower in 1925, or the mail carrier Gert Postel, who pretended to be a psychiatrist named Dr. med. Dr. phil. Clemens Bartholdy in the 1990s, got away with their shenanigans for a while before they were caught. The “Captain of Köpenick” even inspired books and films about his life.

Grandiose claims and ambitious forecasts are part and parcel of any pitch competition and crowdfunding platform. An entrepreneur who describes their start-up idea in a modest and understated way will not convince investors. Perhaps the best example for the principle that entrepreneurs have to fake it till they make it is a contract for delivering an operating system a certain Bill Gates signed with the computer giant IBM in 1980. Gates knew that Microsoft would not be able to develop the software in such a short amount of time. So he acquired a system developed by the company Seattle Computer for 50,000 dollars and slightly modified it to become MS-DOS. He earned billions through this deal, which is considered one of the most lucrative contracts in the history of business.

Any heist movie pales in comparison to the elaborate plans behind the real-life Dresden Green Vault burglary of 2019. Already days before the break-in, the culprits had severed and replaced the iron bars of a window at the historic Green Vault. On the night of the burglary, they disabled all streetlights on Theater Square by placing a burning pot under a junction box in the catacombs of the gauging station below Augustus Bridge. They then pushed a window from its frame and entered the dark Pretiosa Room via a ladder. Heading straight to the Jewel Room, they smashed the glass displays with a hatchet to steal three particularly valuable sets of jewelry dating back to the 18th century. The loot’s material value exceeded 100 million euros.

The complexity, time pressure, and dynamics of a start-up enterprise also require professional, integrated, and sound planning. Entrepreneurs who only rely on their gut feeling as they simultaneously develop technological systems, look for partners and investors, design an organization’s structure, and enter customer segments will often find that things do not go as (insufficiently) planned. It’s no coincidence that business planning is a core component of all entrepreneurship training programs.

Operating outside of legal bounds creates considerable challenges for organized crime. Written documents could constitute evidence. This poses difficulties for management, task allocation, organizational structure, process coordination and rules, instructions and commands, HR development, CRM, knowledge management and transfer, and all aspects of accounting. Against this backdrop, it is hardly surprising that Meyer Lansky, one of the key figures of the US-based Kosher Nostra, is said to have had an astonishing knack for memorizing figures. Arrests and having to deal with competing gangs of mobsters also require fast and coordinated action. This makes organized crime a textbook example for lean, decentralized, and agile structures.

These are properties they share with start-ups, which outplay existing companies that have much more resources at their disposal through their swift and flexible pace.

Analyzing the dark side of entrepreneurship provides a learning opportunity to deepen our understanding of the legitimate light side that creates much good for society. Investigating the tool kits of entrepreneurs can also be useful in the fight against illegal and illegitimate types of business.

According to an anecdote from the 13th century, an official charged with investigating the murder of a farmer in the South of China ordered all 70 farmers of the village to present their sickles. None showed any traces of blood. But the witty official had an idea. He had the blades laid out on a nearby field and watched what would happen. It did not take long for hordes of flies to flock to one of them – a telltale sign. Caught off guard, the blade’s owner confessed to the murder.

The history of crime is full of tales of creative and immensely effective innovations such as fingerprint and DNA analyses, helping investigators showing true entrepreneurial spirit excel at their jobs.

Read the 1st part here - Illegal But Legitimate: What Robin Hood and Uber Have in Common

Read the 2nd part here - Legal but Illegitimate: Gambling, Prostitution, and Tobacco Use